A Chat With Alejandro Jodorowsky

|

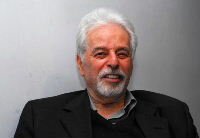

Visionary or madman? Throughout an eclectic career, spanning forty years and just seven films, Chilean born director Alejandro Jodorowsky has been both acclaimed and vilified. With the release of three of his most celebrated films on DVD, and a 6-disc boxset containing soundtracks and a 90min documentary on Jodorowsky, rarely seen work will be available, uncut and uncensored, to baffle and provoke audiences. FilmExposeds Andrew Pragasam went to meet him

Love him or loathe him, theres no one quite like him. His breakthrough work, the almost indescribable, mystical western EL TOPO (1971) has resurfaced to astound a new generation. Thirty years ago, it made him the darling of New Yorks counterculture set, with the likes of JOHN LENNON lavishing praise. Jodorowsky famously declared that what people bring to El Topo is ultimately what they take away. But what does El Topo mean to him? It changed my life, says Jodorowsky. Socially, because I was closed off in Mexico, it opened my door to the world. And it opened my mind, because I realised I need to fight against reality. It changed my character. In many ways, Jodorowskys journey mirrored that of the character he portrayed onscreen. For every action he takes, he changes. His mind is changing, with each step he takes towards the infinite.

El Topos startling climax references the famous image of a Buddhist monks self-immolation in protest at the Vietnam War. A nihilistic act or has El Topo attained enlightenment? On El Topos grave you see bees making honey. In this scene, he is making food for humanity. This food is passed on to his son and his woman, and they will go on to change the world in some way. Christ, Buddha, prophets dont change the world themselves. They make an action, they die and the idea they create goes on to affect humanity.

Now in his mid-seventies, Jodorowskys grey hair and serene demeanour make him seem even more sage-like than in the counterculture days when hippies worshipped El Topo like a sacred text. He began his career performing mime at the circus and later studied under Marcel Marceau. His first film was a mime adaptation of Thomas Manns The Severed Heads, but it was 1968s Fando y Lis that made him. Its stark violence and unsettling surrealism had it banned in Mexico, but it won admirers in the USA. Dennis Hopper adopted its fragmented editing for Easy Rider (1969) and recruited Jodorowsky to edit his follow-up, The Last Movie (1971). An incredible story, but the studio withheld the movie. I would like to see my work.

John Lennons enthusiasm for El Topo, led Beatles manager Allen Klein to distribute the film and arrange a bigger budget for Jodorowskys even more ambitious, THE HOLY MOUNTAIN (1973): a metaphysical fantasy/science fiction adventure in cinemascope. The filmmakers feud with Klein meant both films were difficult to see, until recently. We were fighting for thirty years. Then, I called his son and proposed peace. Were getting old, you know? All I want is for my films to be seen in good condition.

Jodorowskys most audacious project never came to be. He assembled an extraordinary cast and crew to adapt Frank Herberts sci-fi epic, Dune. I had Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, David Carradine, Alain Delon, Udo Kier, Salvador Dali and in the lead, my son Brontis. Each planet was designed by a different artist: H.R. Geiger, Moebius, and Dan OBannon (screenwriter of Alien (1979)) would create the special effects, while Pink Floyd would compose the score. His Hollywood backers, wary of the sheer scale of the project, pulled out. I was in misery, admits Jodorowsky. One day Ill publish the shooting script. Three thousand drawings. And his take on DAVID LYNCHs Dune (1984)? DAVID LYNCH is a true artist, but the movie is very bad. Its not his fault, but the producers (Dino DeLaurentiis). He put an artist in an industrial situation. Bergman had the same problem. All the great directors who worked with DeLaurentiis made their worst pictures.

Jodorowsky and French comics legend Moebius reworked their concepts for Dune into The Third Incal, in many ways his finest achievement. A beguiling mix of esoteric philosophy, sci-fi adventure and Disney-esque whimsy, it launched his secondary career as a comic book auteur. I always wanted to create graphic novels. Theyre a true art form, a graphic art.

Often disparaged by hardcore Jodorowsky fans, Tusk (1980) is a neglected gem. It recounts a young girls bond with a sacred elephant and boasts an extraordinary opening sequence where the elephants birth is intercut with that of the child heroine. The producer said I failed, but it plays on French television. Id like to re-cut it, then it could be very good. In 1989, his Santa Sangre was well received, but The Rainbow Thief (1990) starring PETER O'TOOLE and Omar Sharif suffered from producer interference and remains elusive. Making a movie is never a happy experience. Its always a battle, smiles Jodorowsky, tired but triumphant.

|